Farm Forward Board Member, Jonathan Safran Foer, Encourages Meat Reduction at the Vatican

In the Vatican Gardens after a private audience with the Pope, author and Farm Forward founding board member Jonathan Safran Foer gave a keynote address in response to Pope Francis’s new Apostolic Exhortation, Laudaute Deum. Foer argued that food systems reform and eating fewer animal products are important and necessary modes of addressing climate change. He also discussed the necessity for policy change and individual action in meeting the moment. Below is the text from Foer’s speech.

It is a tremendous honor to participate today. Before having the opportunity to read the text of Pope Francis’s “Laudate Deum,” I had no intention of bringing my one-year-old daughter to this event. But I was so profoundly moved by the wisdom, courage and moral urgency of the Pope’s words, that I wanted her—a representative of my, and our, future—to be present.

In 1942, a twenty-eight-year-old Catholic in the Polish underground, Jan Karski, embarked on a mission to travel from Nazi-occupied Poland to London, and ultimately America, to inform world leaders of what the Germans were perpetrating. In preparation for his journey, he met with several resistance groups, accumulating information and testimonies to bring to the West. In his memoir, he recounts a meeting with the head of the Jewish Socialist Alliance:

The leader gripped my arm with such violence that it ached. I looked into his wild, staring eyes with awe, moved by the deep, unbearable pain in them. “Tell the leaders that this is no case for politics or tactics. Tell them that the Earth must be shaken to its foundation, the world must be aroused. Perhaps then it will wake up, understand, perceive…”

After surviving as perilous a journey as could be imagined, Karski arrived in Washington, D.C., in June 1943. There, he met with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, one of the great legal minds in American history, and himself a Jew. After hearing Karski’s accounts of the clearing of the Warsaw Ghetto and of exterminations in the concentration camps, after asking him a series of increasingly specific questions (“What is the height of the wall that separates the ghetto from the rest of the city?”), Frankfurter paced the room in silence, then took his seat and said, “Mr. Karski, a man like me talking to a man like you must be totally frank. So I must say I am unable to believe what you told me.” When Karski’s colleague pleaded with Frankfurter to accept Karski’s account, Frankfurter responded, “I didn’t say that this young man is lying. I said I am unable to believe him. My mind, my heart, they are made in such a way that I cannot accept it.”

Frankfurter didn’t question the truthfulness of Karski’s story. He didn’t dispute that the Germans were systematically murdering the Jews of Europe—his own relatives. And he didn’t respond that while he was persuaded and horrified, there was nothing he could do. Rather, he admitted not only his inability to believe the truth, but his awareness of that inability. Frankfurter was unable to wake up, understand, perceive.

Our minds and hearts are well built to perform certain tasks, and poorly designed for others. We are good at things like calculating the path of a hurricane, and bad at things like deciding to get out of its way. We excel at taking care of ourselves, and struggle to make the leaps of empathy required to take care of others. The further those “others” are—geographically, in time, and between species—the greater we struggle.

Although many of climate change’s accompanying calamities—extreme weather events, floods and wildfires, displacement and resource scarcity—are vivid, personal, and suggestive of a worsening situation, they often don’t feel that way in aggregate. They often feel abstract, distant, and isolated, rather than like beams of an ever-strengthening narrative. The earth is telling us a story that we seem unable to believe.

Although many of climate change’s accompanying calamities—extreme weather events, floods and wildfires, displacement and resource scarcity—are vivid, personal, and suggestive of a worsening situation, they often don’t feel that way in aggregate. They often feel abstract, distant, and isolated, rather than like beams of an ever-strengthening narrative. The earth is telling us a story that we seem unable to believe.

So-called climate change deniers reject the conclusion that science has reached: the planet is warming because of human activities. But what about those of us who say we accept the reality of human-caused climate change? We may not think the scientists are lying, but do we have the will to believe what they tell us? Such a belief would surely awaken us to the urgent ethical imperative attached to it, shake our collective conscience, and render us willing to make small sacrifices in the present to avoid cataclysmic ones in the future.

Intellectually accepting the truth isn’t virtuous in and of itself. And it won’t save us. As a child, I was often told “you know better” when I did something I shouldn’t have done. Knowing was the difference between a mistake and an offense.

If we accept the factual reality that we are destroying the planet and dooming future generations, but are unable to believe it and change our behaviors in meaningful ways, we reveal ourselves to be just another variety of denier. When the future distinguishes between these two kinds of denial, which will appear to be a grave error and which a sin?

Perhaps the most courageous feature of Pope Francis’s paper is that he pointedly calls us “to move beyond the mentality of appearing to be concerned but not having the courage needed to produce substantial changes.” It is more comfortable to speak about these changes in abstract terms—the kind that make us feel good when advertised on t-shirts or cheered in rallies—than the practical ones that require us to alter our lives. Yes, there are constraints on how quickly and how much we can change, there are conventions and economic realities that limit the parameters of the possible. Yet we remain free to choose among possible options—and there are many within reach that could alter the trajectory of existence.

The most influential decisions will be at the policy level, shaping the practices of nations, but we also can make decisions in our own lives and local institutions that matter more than crude math might suggest. As Pope Francis emphasizes, “Efforts by households to reduce pollution and waste, and to consume with prudence, are creating a new culture”—a culture that is already playing, and will play, a decisive role in rallying larger collective actions. Choosing a form of transportation with lower carbon emissions, or reducing the consumption of animal products, especially meat, are actions that can matter at the individual and the policy level. The power of food system change to alter the climate is particularly noteworthy and only just beginning to be realized.

We need structural change, yes. We need a global shift away from fossil fuels. We need to enforce something akin to a carbon tax, build walkable cities, and rapidly electrify homes and communities from increasingly renewable energy sources. We need to acknowledge the disproportionate obligations of countries, like my own, that have been disproportionately responsible for climate change. We will likely need a political revolution. These changes will require shifts that individuals alone cannot realize. But putting aside the fact that collective revolutions are made up of individuals, led by individuals, and reinforced by individual revolutions, we would have no chance of achieving our goal of limiting environmental destruction if individuals don’t make the very individual decision to live differently: to drive and fly less, to eat less meat, and to do the hard work of believing in both the catastrophe we are creating and our capacity to avert it. Of course it’s true that one person’s decisions will not change the world, but of course it’s true that the sum of hundreds of millions of such decisions will.

This is not to understate the challenge of changing one’s life. I have written two books about ethical eating and still regularly struggle to make choices that reflect my beliefs. It is now clear that this will be a lifelong struggle for me. I began these remarks by mentioning that my daughter is joining me today. We flew here. I made the decision that the carbon expense of this particular trip was worth it. These are the kinds of choices each of us must face, and we won’t arrive at the same answers. What’s needed is not complete agreement, much less purity, but our belief, expressed through our best and most thoughtful efforts.

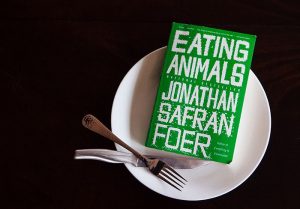

This is not to understate the challenge of changing one’s life. I have written two books about ethical eating and still regularly struggle to make choices that reflect my beliefs. It is now clear that this will be a lifelong struggle for me. I began these remarks by mentioning that my daughter is joining me today. We flew here. I made the decision that the carbon expense of this particular trip was worth it. These are the kinds of choices each of us must face, and we won’t arrive at the same answers. What’s needed is not complete agreement, much less purity, but our belief, expressed through our best and most thoughtful efforts.

Also needed is hope. There is an understandable tendency among those who care to catastrophize. I often wrestle with despair in my own thinking about climate change. We need not despair, and we cannot despair. If we can acknowledge in our hearts what our heads have already concluded about the struggle before us, the courage to change will follow.

Pope Francis addresses his Laudate Deum to “all people of good will,” and this sentiment presides over the document. What does it mean to be a person of good will if not to make ethical choices? What is ecological grace if not the sum of daily, hourly decisions to take a bit less than our hands can hold, to eat other than what we might crave in any given moment, to create limits for ourselves so that we all might be able to share in the bounty? Surely we can now see that the sum of these changes will not be the deprivation some have told us to fear, but the overcoming of a global catastrophe and our most valuable gift to the future.

The Talmud tells of a sage who encountered a man planting a carob tree by the side of the road. He asked the man how long it would take to bear fruit. “Seventy years,” the man replied. “And do you think you will live another seventy years to eat the fruit of this tree?” “Perhaps not,” the man answered. “However, when I was born into this world, I found many carob trees planted by my father and grandfather. Just as they planted trees for me, I am planting trees for my children and grandchildren so they will be able to eat their fruit.”

We often think of our legacy as passing along the things we amass in life, but this must change. The most profound inheritance we bestow is not what we acquire, but the beliefs with which we struggle, the efforts we make to live by them, and perhaps above all, what we are ready to let go of. As St. Francis reminds us: “when you leave this earth, you can take with you nothing that you have received–only what you have given.”